“If you talk to God, you are praying; if God talks to you, you have schizophrenia.”—Thomas Szasz, The Second Sin (1973)

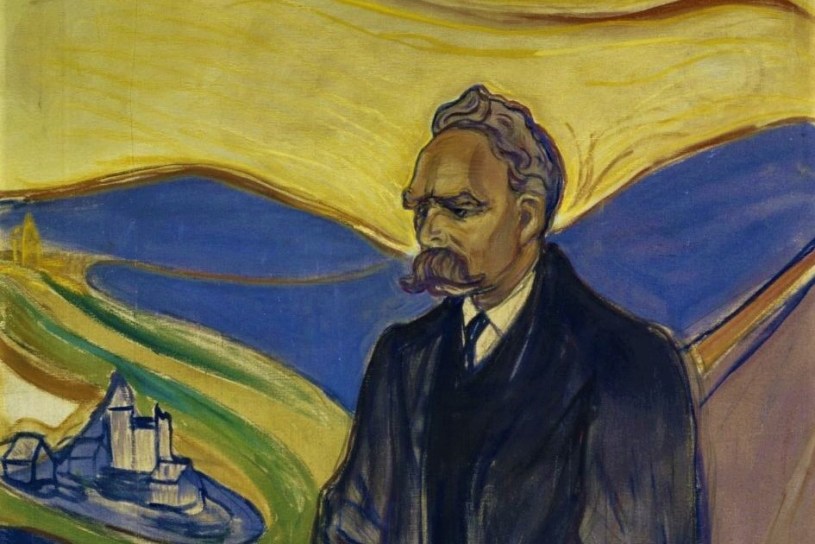

I used to believe in God the way you believe in the existence of your mother and the sky. Like Enoch of old, I knew God. This wasn’t faith or hope or wishful thinking; it was a real relationship. For about three years, between the ages of twelve and fifteen, prayer wasn’t a one-sided exercise for me; it was a two-way conversation. I heard the voice of God. But it didn’t last. One day, without warning, and for no apparent reason, God just stopped talking to me. Never before or since have I felt so completely and utterly lost and alone in the world. Like that madman who mourns the death of God in The Gay Science (1887), I was also profoundly disoriented: “Is there still an up and a down? Aren’t we straying as though through an infinite nothing? Isn’t empty space breathing at us? Hasn’t it got colder? Isn’t night and more night coming again and again?” It was excruciating. Easily the worst experience of my life. But I survived, I muddled through, and I found a way to live happily and well in this Groundhog Day world of ours, a world where each and every day is Holy Saturday.

I haven’t heard the voice of God once since then. Nor do I expect to. Truth be told, I’ve long suspected that this deeply religious period of my life was in fact a rather serious brush with mental illness, brought on by chronic insomnia, raging hormones, and a malfunctioning adolescent brain. And I’m glad to have dodged that bullet. But I’m equally glad to have dodged a psychiatric diagnosis. I’m thankful to my uncle Peter for sharing his faith with me when he did. Pentecostalism provided me with a narrative framework within which to make sense of what was happening to me, as well as a supportive religious community that normalized (and, indeed, often valorized) the strange experiences I was having. If it wasn’t for Peter, I’d probably be a drugged out shell of a man now: in and out of psychiatric hospitals, living at the margins of society, without family, without work, without self-respect, without dignity, without purpose.

Psychiatry’s current conception of “schizophrenia” is deeply flawed and thoroughly incomplete. Even so, it’s surely truer, far truer, than Pentecostalism’s supernatural understanding of the same set of symptoms. But this is largely irrelevant to someone who’s hearing voices from time to time. For them, the relevant questions are more likely to be: Whose treatment is more humane? Which narrative is more likely to allow me to remain part of my community? Which diagnosis is more likely to allow me to live a more or less regular, productive life? Which will permit me to remain a fully functional member of my society? These questions pretty much answer themselves, and that’s the problem. Schizophrenia is hard, no doubt about that. But what we do to schizophrenics is often much harder than schizophrenia.

—John Faithful Hamer

Profound and honest piece. Recently here in Cork we had presentations to the psychology and psychiatry community from the Hearing Voices group in Ireland. They are an interesting bunch–funny and insightful. Its good that these things are coming out of the shadows and we are able to talk abou them

LikeLiked by 1 person