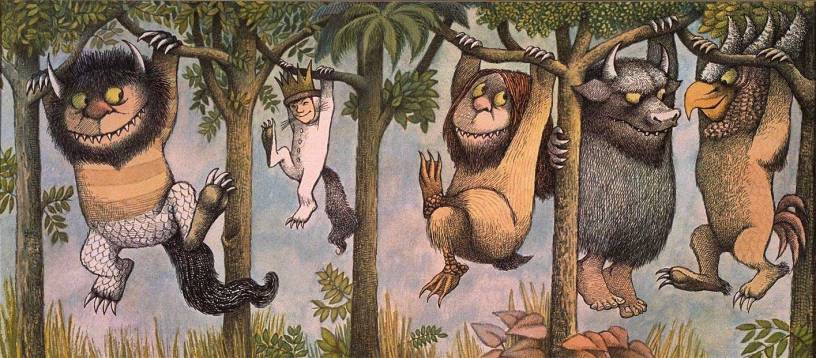

In the annals of childhood storytelling and imaginative play, one of my favorite books is Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. Despite being banned by most libraries and receiving universally negative reviews from critics when it was first published in 1963, the book quickly became and has remained one of the most popular and well-loved staples of children’s literature in North America. And like many kids who loved Max and the wild things, I’m sure that at least some of its popularity can be explained by how well it resonated with the imaginary places I constructed in childhood to escape the consequences of being banished to my dull room as punishment for some ill-advised behavior. Yet I’m also convinced, more recently, that the Wild Things and their world are indicative of a far more pervasive and omnipresent part of our culture—one which imagines the wild as a far-off, exotic, and ‘natural’ landscape as a safety valve to escape the pressures of our post-industrial and denatured lives. And while the temptation to envision an unspoiled world in the face of the complex environmental challenges of the 21st century is certainly understandable, responding to them effectively begins with imagining this narrative differently.

In the annals of childhood storytelling and imaginative play, one of my favorite books is Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. Despite being banned by most libraries and receiving universally negative reviews from critics when it was first published in 1963, the book quickly became and has remained one of the most popular and well-loved staples of children’s literature in North America. And like many kids who loved Max and the wild things, I’m sure that at least some of its popularity can be explained by how well it resonated with the imaginary places I constructed in childhood to escape the consequences of being banished to my dull room as punishment for some ill-advised behavior. Yet I’m also convinced, more recently, that the Wild Things and their world are indicative of a far more pervasive and omnipresent part of our culture—one which imagines the wild as a far-off, exotic, and ‘natural’ landscape as a safety valve to escape the pressures of our post-industrial and denatured lives. And while the temptation to envision an unspoiled world in the face of the complex environmental challenges of the 21st century is certainly understandable, responding to them effectively begins with imagining this narrative differently.

Why? Because narratives, stories, and myths matter: they shape the way that we think about one another and the world. They shape the way we, even as children, imagine certain places, spaces and ideas. And when it comes to nature, the environment, and where the wild things are, they have very real consequences for the way we understand, see and act in the world. Let me illustrate this with one example from a setting that is probably familiar to you: the public park.

Last summer, my husband and I stopped with our two boys at a playground on a break from walking around the much larger public park in our hometown. On the playground, they joined other kids on the gym equipment while we took stock of the area for a place to sit. In the process, we noticed and sat near a huge supply of wild black raspberry bushes with ripe fruit lining the cultivated playground lawn. As we watched other caregivers, parents, and careful folk unpack their Tupperware containers or other brightly colored snack-themed paraphernalia, my husband and I turned around and picked some of those black raspberries for our kids, who then devoured them. Yet no one else did, even though there was more than enough for everyone, including all of the adults and their friends, to go around. And when the kids were done, we left the gym equipment to explore the paths through and around the trees for salamanders, snakes, butterflies and all manner of bugs. Yet while the playground was full with families and we encountered other adults with the occasional kid on those paths, our boys turned over rocks, climbed trees and scaled logs virtually alone. There was wildlife and wild raspberries aplenty in this very public and very popular park. But no one seemed aware of or interested in them.

Of course, it would be a mistake to assume that all of the parents and participants we encountered want to find bugs or chase butterflies or check out the berries with their kids in the park. But it’s a bigger mistake to assume that they don’t value the trees or butterflies or berries either. After all, it is not as if we don’t value nature, or wildlife, just because the kids are at the playground that day. In fact, given all of the ‘new research’ dedicated to extolling the virtues of the forest in fashionable parenting manuals these days, I would venture to guess that most families and parents in attendance at the park that day value the lessons of nature and the wild more than their parents’ generation did. We just don’t tend to look for them in our local park.

Of course, it would be a mistake to assume that all of the parents and participants we encountered want to find bugs or chase butterflies or check out the berries with their kids in the park. But it’s a bigger mistake to assume that they don’t value the trees or butterflies or berries either. After all, it is not as if we don’t value nature, or wildlife, just because the kids are at the playground that day. In fact, given all of the ‘new research’ dedicated to extolling the virtues of the forest in fashionable parenting manuals these days, I would venture to guess that most families and parents in attendance at the park that day value the lessons of nature and the wild more than their parents’ generation did. We just don’t tend to look for them in our local park.

It is also probably safe to say that many, or even most, of the adults we encountered would probably not recognize the fruit on those bushes as black raspberries, or, if they did, would not be willing to pick and eat them directly from those branches. And many or most who might have been interested in the wildlife probably did not know how or where to find a red-backed salamander. So our separation from the natural world, including a basic knowledge of how to recognize food, plants or wildlife that are native to the park and everyday surroundings is certainly part of the equation. And sure, my husband and I have some experience in recognizing black raspberry bushes, so perhaps this makes sense.

It is also probably safe to say that many, or even most, of the adults we encountered would probably not recognize the fruit on those bushes as black raspberries, or, if they did, would not be willing to pick and eat them directly from those branches. And many or most who might have been interested in the wildlife probably did not know how or where to find a red-backed salamander. So our separation from the natural world, including a basic knowledge of how to recognize food, plants or wildlife that are native to the park and everyday surroundings is certainly part of the equation. And sure, my husband and I have some experience in recognizing black raspberry bushes, so perhaps this makes sense.

But lack of knowledge doesn’t explain the undeniable fact that it wasn’t because the adults at the park on that hot summer day ignored or dismissed or distrusted the wild black raspberries at the edge of the playground that they went uneaten. It was, rather, because they literally didn’t see what was right behind them, didn’t notice the bushes and trees that surrounded the playground—that, in short, the raspberries went uneaten because because they were invisible. My husband and I were the only adults, in fact, to approach the bushes in close enough proximity to either recognize or contemplate whether the fruit we saw on them was edible.

But lack of knowledge doesn’t explain the undeniable fact that it wasn’t because the adults at the park on that hot summer day ignored or dismissed or distrusted the wild black raspberries at the edge of the playground that they went uneaten. It was, rather, because they literally didn’t see what was right behind them, didn’t notice the bushes and trees that surrounded the playground—that, in short, the raspberries went uneaten because because they were invisible. My husband and I were the only adults, in fact, to approach the bushes in close enough proximity to either recognize or contemplate whether the fruit we saw on them was edible.

So I suppose it would be useful to here entertain the sociological explanations for parental tunnel vision, including lack of time, busy schedules, helicopter parenting and a host of other pressures that keep us from spending time in or noticing the more unstructured aspects of park play. But, again, that only gets us so far, because busy schedules get cleared for nature and wildlife, if even only on occasion.

So this leaves us with the final and most important question: if we value nature, and wildlife, and/or the natural environment, or if we value hobbies and past times because they enable us to get out into ‘nature’, and/or if we make sure to spend time going camping, hiking, or ‘getting away’ from urban or suburban life to greener pastures and trees when possible, why do we neglect the wild side of our local public parks?

So this leaves us with the final and most important question: if we value nature, and wildlife, and/or the natural environment, or if we value hobbies and past times because they enable us to get out into ‘nature’, and/or if we make sure to spend time going camping, hiking, or ‘getting away’ from urban or suburban life to greener pastures and trees when possible, why do we neglect the wild side of our local public parks?

The answer takes us back to Sendak: wildlife, wild things, and ‘nature’ are not found in the urban or suburban park, but away from human life, in camp grounds and on hiking trails, in the ‘country’, and, most importantly, removed from everyday human life and experience. We ‘escape’ to nature where it is valued for its capacity to be unspoiled—that is, untouched or unmarked by human habitation. And the more unspoiled, the more fantastic, and the more exotic, the more we value the ‘wild’ of it all, the more we think of it as a cure for what’s wrong in our lives, and the more we feel the need to protect it and the parts of ourselves that find refuge there.

The answer takes us back to Sendak: wildlife, wild things, and ‘nature’ are not found in the urban or suburban park, but away from human life, in camp grounds and on hiking trails, in the ‘country’, and, most importantly, removed from everyday human life and experience. We ‘escape’ to nature where it is valued for its capacity to be unspoiled—that is, untouched or unmarked by human habitation. And the more unspoiled, the more fantastic, and the more exotic, the more we value the ‘wild’ of it all, the more we think of it as a cure for what’s wrong in our lives, and the more we feel the need to protect it and the parts of ourselves that find refuge there.

The problem with this, of course, as the 19th century conservationists eventually realized, is that the ‘environment’ and what is ‘natural’ is not a some destination merely to be set aside for future enjoyment. Downwind or downstream pollution do not respect either political or social boundaries, and we ignore the impact of these, as well as the issues of sanitation, air quality, and job safety—that is, human problems—that directly shape their intensity and direction, at our peril. But we also rob ourselves of the opportunity to wonder about, and in, the beauty and refuge of experiencing wildlife and nature in our everyday lives. In our park, all we needed to do was pay attention to the trees, bushes, and the entirety of the green space and park landscape surrounding us that day to find it. And all one ever needs to do is slow down, get off the bike, treat the path as the destination rather than the route to get there, and explore. And what happens if you do so? You find that there is a wild side, even in the center of a post-industrial city, not just rife with wild black (and red) raspberries, but of snakes and salamanders, of toads and butterflies that settle on and under your feet, and of trees or logs or bogs that can be crossed, or climbed, or tested at will.

But the deeper and more meaningful implications of this—of fully recognizing and exploring your neighborhood, park and everyday life as part of the natural world—are far more radical. Recognizing where the wild things are at the edges of the playground, on the path to the gym equipment, and in the everyday environments of our daily lives inheres deeper, more meaningful lessons concerning the role of knowledge, the significance of humility, and the place of natural limits on our world than any weekend camping expedition. Because paying attention to what is wild in our everyday lives ultimately makes us responsible for making sure what we find, whether they are bees or blueberry bushes, will be valued and protected as well.

I still love Sendak and the thought of escaping to far off places with the Wild Things. And I don’t think we should stop valuing the beauty and power of the natural landscapes and places to transform us. But we do need stories that enable us to imagine and thus see the wild spaces all around us to help us understand that we are, in fact, connected to and part of those landscapes. Perhaps in doing so, we can begin thinking differently about how to achieve a more sustainable world.

—Anna-Liisa Aunio

Reblogged this on Tree-Magazine !.

LikeLike